The following is a preview of the Financial Intelligence Guide for Social Enterprises. For complete worksheet features and supplementary appendices, please download the attached files located on the left hand side.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Core Financial Management Practices for any Business

Part 2: Unique Issues for Social Enterprises

Part 3: Developing a True Cost Picture

Part 4: Going Forward – Using the True Cost Picture Workbook and other Tools

Introduction

Good financial monitoring systems support successful financial management. This involves getting the information that can provide you with the most insight into your operations and financial position. In other words, getting the right 'financial intelligence'. Developing strong financial reporting practices can help achieve the following benefits:

Greater success of enterprises through improved managerial decision making

All businesses, including social enterprises, require accurate and timely financial and operational performance data to inform decision-making about enterprise operations and growth.

The Real Story – making the case for social enterprises

A clear accounting of the costs and profitability of enterprises is critical to demonstrating the value of social enterprise in communities and to make a case for investment and support from government and private sector investors. For example, it can be easier to fundraise when you can clearly describe the costs that relate to your social/environmental mission.

This guide introduces some of the financial management fundamentals that you will need to successfully measure financial performance and grow your social enterprise. The guide is by no means comprehensive and does not address CICA financial accounting standards. We encourage you to utilize the additional resources recommended in Part 5 and to consult with accounting and financial professionals. The guide is divided in four parts:

- Core Financial Management Practices for any Business.

- Unique Issues for Social Enterprise. Social enterprises are unique hybrid entities with financial management and reporting needs that are not adequately addressed by either non-profit or business accounting and financial reporting systems and practices. This section addresses the unique issues and needs of social enterprises.

- Developing a True Cost Picture. Good information provides the groundwork for business and mission sustainability. Capturing all costs and distinguishing between core business costs and social costs will give you the information you need to more clearly assess both business and mission performance.

- Going Forward with the True Cost Picture. Step-by-step instructions help you to implement some of the concepts covered in this guide leading to a “Double Bottom-Line” presentation which highlights the dual purpose of a social enterprise.

The guide refers to a number of tools that you can use in your enterprise to improve your financial intelligence. The term "social" used in such terms as social enterprise and social objectives encompasses social, environmental and cultural meanings.

Part 1: Core Financial Management Practices for any Business

Financial intelligence in any business starts with capturing information (the daily recordkeeping of sales, purchases and other transactions) and presenting and interpreting that information through key financial statements – the income statement (profit and loss statement), the balance sheet, the cash flow statement, and operating budget. Collectively, these help you to assess past performance, identify risks to the financial position of the business, and to find opportunities to improve performance.

This section describes key considerations in setting up good financial monitoring for any business including who should be involved, policies, daily record keeping and the preparation of financial statements.

People and Policies

The following people are critical to smooth financial monitoring:

A bookkeeper manages the daily recording of transactions, maintains a general ledger, maintains cash records and other records that are specific to your business.

An accountant can help set up your books and choose appropriate accounting software that best suits your business needs, review and recommend accounting policies and procedures, help develop your budget, and should be involved in closing the books at year end and preparing annual financial statements for external purposes (board review, income tax, banking, funding).

Enterprise managers should be actively involved in the financial tracking and reporting of the enterprise, and should be able to review financial information frequently.

Internal Controls. Next to having the right staffing, having clear procedures and controls in place is critical for successful and responsible financial management. A system of internal controls would include appropriate signing authorities (spending, timesheets, billings, and contracts), having a clear paperwork or audit trail, separation of duties, and established review and reporting policies.

Record Keeping

Day-to-day Records

As a business, you will record your day-to-day sales, purchases, and other transactions. These records are kept in the general ledger which serves as the permanent record of all financial transactions. Supporting journals typically include sales and revenue transactions, cash transactions, accounts receivable, and accounts payable (the latter two are kept if the enterprise uses and extends credit). Different reports can be readily generated from this information depending on your software program. These include:

Customer Reports: e.g. Customer List, Aged Accounts Receivable Reports, Detailed Sales Report, Sales Transactions, Receipt Transactions

Vendor Reports: e.g. Vendor List, Aged Reports, Detailed Purchases Report, Purchase Transactions, Payment Transactions

Inventory Reports: e.g. Inventory Valuation and Production Reports

Payroll Reports: e.g. Employee List, Payroll Summary, Detailed Payroll Report, Payroll Transactions

Accounting Period

For accounting purposes, organizations generally use a twelve month fiscal period such as January 1 to December 31 or July 1 to June 30. The accounting period you select doesn't have to coincide with the calendar year; a seasonal business, for example, might close its year at the end of the season. Choosing your year end will depend upon the nature or cycle of your business, your funders' information needs, availability of resources, and/or possible tax considerations.

Accounting Method

There are two common accounting methods for recording transactions: cash and accrual. Cash basis accounting recognizes transactions when the cash changes hands. Accrual basis accounting recognizes income when it is earned and matches expenses to income. Under the accrual method, a bill that must be paid by the organization is included as a liability, and money that the organization is owed is listed as an asset on financial statements. Accrual basis accounting gives a more accurate picture of financial performance than cash basis accounting.

Accounting Policies

The objective of financial reporting is to communicate useful and relevant information to managers and stakeholders. Accounting policies are specific methods and assumptions chosen for the measurement, presentation and disclosure of accounting information that will best reflect the economic substance of transactions and conform with fundamental financial accounting principles (see the box above). These include:

- policies for capitalization and amortization of capital assets,

- inventory valuation, treatment of development costs (whether and how investments made in developing a product are amortized over the life of the revenue stream it generates),

- decisions about what to accrue as an asset or liability (for example prepaid assets or deferred contributions), and

- when to recognize revenue (that is, when have you satisfied your obligations and clearly “earned” your revenue).

You will need to consider every type of transaction that has a significant impact on your financial picture and determine the most appropriate and meaningful method of measurement and presentation for your type of business.

Basic Accounting Principals Materiality – How significant is the information to users and the decision-making process? What impact will that information have on their decisions? |

Accounting Software

There are many excellent accounting and database software packages that can be readily purchased and implemented by your business. These packages may also include useful management tools such as budgeting, inventory tracking, payroll processing and invoicing. If the accounting department is unable to commit to the level of tracking that you desire (for example, tracking sales and gross profit by specific product), information can also be collected and analyzed using spreadsheets in conjunction with accounting software. Many software tools and technical support are available to non-profit organizations, free of charge, through Techsoup.org, a valuable resource for your organization.

Financial Reporting Package

Financial statements are prepared periodically based on basic financial information that is recorded. The timing of these statements should reflect the operational needs of the enterprise - monthly is recommended (with the potential for updates weekly or even daily). This differs from reporting in non-profit programs, in which financial statements are typically provided on a quarterly basis to executive management and the board. Frequent reporting on the financial activity of a business is important. Without timely information, trends such as growing inventory, uncollected receivables, or falling sales, may go undetected without appropriate management response. Regular reporting and review of the reporting package by managers, the executive director and board of directors establishes oversight, accountability and serves as an important internal control in any organization.

Your financial reporting package should provide a complete picture of the social enterprise's financial performance. Key components of the package and uses of that information include:

- Budget – financial planning and monitoring

- Balance Sheet – understanding your current financial position

- Profit and Loss Statement – understanding the results of operations, sources of earnings, and profitability

- Cash Flow Statement – understanding and meeting cash flow needs

- Financial Snapshot – summarizing key performance indicators based on financial objectives

Your Budget

Budgeting lies at the foundation of every operational plan. Your budget, normally prepared on an annual basis and broken down by month, is a critical planning tool projecting all of your activities (revenues/inflows and expenses/outflows) for a particular period. A budget is developed based on historical trends and future expectations and targets, and should draw from the knowledge and experience of your key accounting, operations and marketing staff. Not only is a budget useful for monitoring actual performance, the process itself can help to identify issues such as cash flow problems or pricing strategy.

Cash flow budgeting is another fundamental component of financial planning. Due to timing differences between investment in inventory, earning revenue and actual cash receipts, you may be profitable as a business but still have difficulty meeting your payment obligations. Planning and managing the timing of your cash flows will ensure that you are able to meet all of your financial obligations, whether by improving your working capital management or relying on short term financing alternatives such as a line of credit.

Your Balance Sheet

The balance sheet (also called a statement of financial position) is a financial 'picture' of your business at a given point in time showing what you own (assets) and what you owe (liabilities) in relation to your overall net worth (equity). The statement also shows the extent to which your business is financed by internal (working) capital or external (debt) sources. Because the balance sheet conveys the big picture, it is an important statement from the perspective of potential investors, creditors and funders.

Your Profit and Loss Statement

The profit and loss statement (also referred to as an income statement or operating statement) is used to assess the enterprise's profitability over a period of time. It reports revenues, expenses, gains, losses and net income for a specific period. This statement is useful to managers and funders for tracking profit margins, monitoring budget variances, performance benchmarking and predicting future performance. There are many accounting policy options and reporting objectives to be considered when profit and loss statements are prepared, so as to best convey economic reality and maximize insights. Some examples are highlighted below:

Costs of Sales and Gross Margin: Setting up your profit and loss statement so that you calculate a gross margin is valuable. Gross profit is the difference between sales revenue and direct costs of sales. Gross profit is a key number for business providing insight into basic profitability of your product or service, production efficiency, break-even point (or level of sales you need to achieve to actually start to make a profit), contribution analysis (how much each additional unit of production with contribute to overhead), and industry benchmarking.

Depreciation Policy: Depreciation is the process by which a capital asset's cost is allocated over the duration of its useful life. An appropriate depreciation policy (method and rate of depreciation), based on useful life and residual value of the asset, will reflect the true cost of using that asset each period. Depreciation is also an important indicator to plan ahead for eventual asset replacement and necessary future outlays.

Groupings and Level of Detail: Ensure that the groupings and the level of detail in your profit and loss statement is useful to you. For instance, is your profit and loss statement broken out into categories that are useful to you, and with sufficient detail? You may want to report separately certain revenue sources or expenses if they are significant in terms of dollar value or decision drivers. Tracking products or services separately allows you to understand the profit margins of different products, and to choose an appropriate and most profitable sales mix. You may also want to separate your core business and social mission activities (discussed more extensively under “Developing a True Cost Picture”, Part 3 of this guide).

Your Cash Flow Statement

Understanding and managing your cash flow is crucial to successfully running a business. The cash flow statement helps in assessing the timing, nature and predictability of future cash flows and ultimately your ability to pay your bills. It shows, over a specific period, how cash is generated and used in the various activities of the business including operations, financing and investing and the net cash surplus or shortfall for that period. A cash flow statement can give you a lot of information. For example, if cash from operating activities is consistently lower than net income, a red flag would be raised as to why income is not translating into cash. Perhaps cash is tied up in inventory or receivables and not sufficiently available to meet payroll or supplier obligations. If the enterprise is consistently creating more cash than it is using, the enterprise may be able to reduce its dependence on external funding or increase its mission-related programming (directed at its social, environmental and/or cultural objectives).

For the purposes of a cash flow statement, cash is defined as both cash and 'cash equivalents' (assets that can be readily converted into cash). The statement can be derived using the Direct Method (showing receipts from customers and payments to suppliers, employees, government, and so on) or the Indirect Method (by starting with an income statement and reversing out non-cash items). The indirect method is easier to generate but perhaps not as meaningful as the direct method.

Your Financial Snapshot

What goals do you have for the business and financial success of your social enterprise? What key performance indicators will help you measure achievement of these goals? Does your current accounting system capture and report the information needed to measure performance against those goals? The answers to these questions will have been articulated and form part of the mapping you may have completed in the Demonstrating Value Workbook.

Specific financial goals may include

- Diversify and expand customer base to be less reliant on a few key customers.

- Improve ability to pay expenses in a timely manner.

- Improve operational efficiency.

- Develop new products which provide greater profit margin.

- Reduce reliance on external funding.

Your financial snapshot (as part of your comprehensive Performance Snapshot) should tell your financial story by presenting to stakeholders key information in a format that is easy to access, interpret and use. The snapshot can be a printed document or an electronic dashboard. This presentation could include key financial ratios (see the complementary guide “Using Financial Ratios to Measure Performance”) or other financial results.

How to use Financial Statements

The information in your financial statements can be much more meaningful if it relates to your budget projections, historical trends, and to other firms (benchmarking). The following questions may help you to analyze financial statements.

- What was the financial performance over the past year?

- In what ways and for what reasons was performance different from the budget? Can you explain the variances?

- What financial implications must be taken into account when planning for the upcoming year?

- Are there any unfavourable trends and tendencies in your business's operations? If you sell more than one major product, analyze the relative contribution by each product line or service. You can also look at the relative burden of expenses by each product or service.

- How does your business compare with that of other similar businesses? (Free benchmarking data for small business is available at "Performance Plus" at www.sme.ic.gc.ca; data can also be purchased through the Risk Management Association (formally known as Robert Morris Associates), and Dun and Bradstreet).

Using Financial Ratios

Ratio analysis is a useful management tool that can help improve your understanding of financial results and trends over time, and provide key indicators of organizational performance. Financial ratios derived from the balance sheet provide important indicators of financial health. Financial strength ratios, such as the working capital and debt-to-equity ratios, provide information on the company's ability to meet its obligations and how they are leveraged. This can give investors and funders an idea of how financially stable the company is and how the enterprise finances itself. Activity ratios focus mainly on current accounts to show how well the company manages its operating cycle (which include receivables, inventory and payables). These ratios can provide insight into the company's operational efficiency. (For more information on ratio analysis, see the Financial Ratio Analysis Guide)

Part 2: Unique Issues for Social Enterprises

Financial Goals

The primary financial goal of a standard business is profitability. A social enterprise may have profitability as its goal, or it may not. For instance, your goal may be to be financially sustainable so that your sales revenue covers both your standard business costs and the extra costs you incur to pursue your social, environmental and/or cultural mission. (We refer to these as “social costs”) In this case, your goal is to have no funding support, either from a non-profit parent organization or from outside investors. Another goal could be to operate with some outside funding over the long term. As a social enterprise, it is important to be clear about your financial goals, and to interpret your financial statements accordingly. In summary, these goals could be:

Self-Sufficiency: Business revenues will cover all expenses.

Profitability: Business revenues will exceed expenses. A profit target could be defined.

Contribution: Business revenues will contribute to costs. (e.g. Business revenues may cover business expenses, but not the social costs associated with your mission). The remainder is covered by other revenue sources such as re-occurring grant. A target could be defined for this.

Your financial goals should be realistic and can change as you develop.

Organizational Structure and Philosophy

A social enterprise often operates as a division of a parent non-profit agency where running a business is often new or unfamiliar territory. Here are some specific issues to watch for:

Business discipline: Even though a social enterprise's definition of “success” cannot be measured in pure economic terms, it is important to maintain a disciplined approach to business and keep sight of business “success” and “profitability”. Many social enterprises are willing to bear losses as a social cost of their business but these concepts must be kept very separate for a business to remain sustainable.

Centralized accounting: Centralized accounting and reporting systems of parent non-profits are generally set up to meet funder needs and audit requirements but limit the ability to analyze business performance due to the timing and nature of reports. Financial performance is quite critical to a business manager in planning and assessing day-to-day operations.

Resource limitations: There may be resistance by a non-profit parent agency to separate accounts due to resources limitations or possible complications to cash flow management.

Clear and Separate Program Reporting: It is important to clearly delineate boundaries between the non-profit parent and its various programs (which may include the operation of a small business) so that costs are appropriately allocated between the various programs. For example, if the parent agency runs a small for-profit business for vocational training purposes but also operates traditional non-profit programs to provide job-skills training, some of the social costs of running the business would be borne by the parent. If the social enterprise is self-contained with a dual purpose (to raise money and achieve social objectives) then it could have a double bottom line (business profit and profit after social costs).

Expertise: Social enterprise managers may not come from a business background and therefore will face a learning curve to acquire the necessary management and financial skills to run a business. They may require specialized training and the support of qualified accounting staff.

Accounting Issues

Social enterprises need financial information about the cost of their core business operations as well as the social or mission-related cost of doing business. Without differentiating between business and social costs and capturing all costs relevant to their operations, it is impossible to know whether the enterprise is actually succeeding or failing as a stand-alone business and to what extent the enterprise is contributing to or drawing resources from the parent or other programs.

Overstating profits: Profitability of a social enterprise is often overstated due to a tendency to not account for non-cash contributions of goods and services or costs borne by the parent organization such as overhead, start-up costs and capital investment.

Social costs: Social enterprises will incur additional “social costs” above and beyond pure business costs as a result of their mission-related purpose. The ability to track and articulate social costs can help an organization isolate and assess its business performance, better understand its required revenue mix (sales and grants) and to make a case for government or funder investment in operating shortfalls.

Part 3: Developing a True Cost Picture

Introduction

Good information provides the groundwork for good decisions. Your management team and stakeholders rely on clear, relevant, complete and timely financial information to support strategic and operational decision making related to both business and mission related activities.

True cost accounting is a cost accounting approach that aims to capture all costs of the social enterprise and to classify costs and revenues in a way that accurately tracks financial performance and provides meaningful financial information to stakeholders. This involves a identifying all relevant economic inputs in the social enterprise and then to differentiate costs according to your needs.

Don’t be caught up by the jargon – true cost accounting is simply the application of basic accounting principles in the context of a social enterprise. By understanding those underlying principles and the unique characteristics of social enterprise, you will be able to create your own true cost picture. This section and the accompanying True Cost Picture Workbook will provide a systematic approach to identifying, quantifying and reporting all of the costs of a social enterprise. Ultimately, your organization's accounting policies and systems will be designed to capture and measure your true cost picture.

TRUE COST = GOOD DECISIONS For managers, true cost accounting:

For executive team and board, true cost accounting helps you understand:

For funders and community partners, true cost accounting can help show:

|

A Closer Look at Your Costs

The main objective of cost accounting is to allocate all relevant costs to the appropriate activity or cost objective, that is, any activity for which separate measurement of costs is desired such as a product line, providing a service, or other program or activity.

Costs behave differently and can be presented in different ways to support whatever decisions you are making. An executive director may need information to make resource allocation decisions while an operations manager may need daily information to assess production efficiency. Your accounting system should be designed in a way that supports your critical decision needs. Here are some considerations in looking at and breaking down costs:

- Classify and organize your accounts to suit your situation and needs

- Distinguish between fixed and variable costs; direct and indirect costs

- Look for hidden costs and contributions

- Distinguish your social costs from your business costs

Each of these considerations is discussed in more detail below.

Classification of costs and organization of accounts

Are your revenues and costs broken out in categories that are useful to you, and with sufficient level of detail? You may want to separate out costs that represent a significant segment or line of your business (for example, by contract or product line). Tracking specific products or services allows you to understand the profit margins of different products or services and to determine an optimal sales mix. It may also be useful and of more predictive value to distinguish between recurring revenue sources (for example, sales) from income sources that are non-recurring (such as grants).

When determining the classification of revenues and costs, think about what matters to your business and mission. For instance, if you are a social enterprise that employs people with barriers to employment, you may want to track these employee costs separately. Here are some things to consider when classifying costs:

- What are the indicators identified in your performance snapshot and what costs significantly impact those metrics?

- What are the most important cost drivers in your operations? For example, in a production process your direct labour cost, machinery use, or material wastage may be primary cost drivers and have the most impact on profitability?

- Where are you vulnerable, for example, to cost fluctuations or market competition?

- What are the important operational functions (example production, administration, marketing, support programs)?

- What costs are relevant to your mission, for example target employees?

- Are your accounts ranked in order of significance?

- Do you distinguish between revenue sources? Recurring v. One-time / Long term v. Short term / Business income v. Grant income / Restricted v. Unrestricted

Direct Costs and Indirect Costs

Direct Costs - can be traced directly to a particular activity, such as materials or supplies used to make a product, and can be assigned to that activity relatively easily with a high degree of accuracy. Although direct costs are generally also variable costs (costs that vary in direct relation to level of activity such as raw materials and labour), this is not always true. For example, if an entire building is used for manufacturing, rent would be a direct cost and applied to cost of sales even though it is a fixed cost. Depreciation of manufacturing equipment will not vary with production levels but is directly attributable to production. Production supervisory staff may be salaried full time employees and the cost is fixed no matter what the level of production activity.

Examples of direct costs:

- Raw materials

- Production and supervisory wages

- Production facility rent and maintenance

- Tools and amortization of capital assets

- Labour Recruitment costs

- Insurance

Variable costs are generally controllable in the short term. Understanding their behaviour will assist in making short term decisions such as contribution analysis (how increased production can contribute to overhead), or sensitivity analysis (how price changes or labour rate changes will affect profitability).

Indirect Costs – are costs integral to running the business but cannot be readily tied to a particular activity or output. These are costs that generally require allocation amongst different activities. While there is a tendency for indirect costs to also be fixed costs (costs that will not vary in the short term or within a defined range of activity), this is not always the case (see example cited above). In an organization where overheads and other indirect costs are shared amongst programs and activities, a reasonable mechanism should be determined to fairly distribute these shared costs to properly reflect the true cost of that activity. These costs are also important factors in assessing profitability and optimal allocation of an organization's resources.

Examples of indirect costs:

- Heat, electricity, telephone and other utilities

- Administrative and accounting

- Marketing

- Portion of governance and strategic development costs

- Portion of general fundraising activities

- Banking and finance charges

Looking for Hidden Costs and Contributions

Hidden Costs = resources used or costs incurred in the normal course of business that are not directly paid for or recorded by the enterprise (examples include donated or discounted materials or labour, support from a parent organization). |

One of the challenges of social enterprises is to identify all costs integral to the core business and mission activities. In addition to the obvious identifiable costs, there may be a number “hidden” costs and in-kind contributions that you do not pay for directly. If these costs are integral components of your business activity, then they should be accounted for in order to reflect your true cost picture. This is particularly important when determining a competitive pricing policy or future funding needs to sustain your business in the long term.

Information about the sources and value of all contributions will help stakeholders:

|

The following criteria must be applied when deciding which costs to recognize:

- Goods or services must be used in the normal course of your business

- You would have purchased these goods or services if they were not otherwise provided

- Fair (market) value can be reasonably estimated

- Focus on identifying costs that may be significant to your decision-making process

The following are some examples of hidden costs and contributions. The Identifying Hidden Costs and Contributions Worksheet provides a step-by step approach to help you identify and quantify significant hidden costs in your organization.

Non-cash contributions:

- Volunteer or discounted services

- Discounted or donated goods and materials

- Donated equipment

Support from your non-profit parent organization:

- Shared receptionist service

- Advertising

- Website design

- Office supplies

- Accounting services

- Management staff costs and benefits

- Printer/copier

Back end or contingency costs (future obligations)

One of the best ways to measure contributions is to look at comparable market values and labour rates. For more information on how to estimate the value of labour, see:

- Heritage Canada, How to Estimate the Economic Contribution of Volunteer Work

- University of Toronto, The Volunteer Value Added Website

Distinguishing Social Costs from Business Costs

Social Costs = premiums or additional costs incurred above and beyond normal business costs due to the social, environmental and/or cultural mandate of the enterprise (examples include wage premiums, lower productivity, additional training and support, discounted pricing) What isn't a social cost – normal training costs even if there is a benefit to targeted employees |

Differentiating “social” costs from “pure business” costs can help you better plan and manage the multiple bottom-lines of enterprise performance. Social costs refer to those costs that are related specifically to pursuing your mission, and which distinguish you from a standard business (for instance, because of what you sell, who you sell to, where you are located, who you employ, or how you manage material inputs, energy, transportation and waste). While we call this social costs, it equally relates to costs to pursuing environmental and cultural objectives as well.

As a result of their mission-related purpose, social enterprises will incur additional “social costs” or may receive income subsidies above and beyond pure business costs and revenues.

Why should an enterprise distinguish social costs from business costs?

|

The following are some examples of social costs. The Identifying Social Costs Worksheet provides a step-by step approach to help you identify and quantify significant social costs in your organization.

- Wage rate premiums for targeted groups

- Extra management or supervisory time

- Time spent counseling employees (personal or job-related)

- Wastage

- Lower level of employee productivity/efficiency (be careful not to include inefficiencies inherent in normal business)

- Increased employee turnover

- High insurance rates

- Time devoted to non-profit or funder-related activities (development staff securing donations or grants for the business, business manager making presentations to board or participating in policy meetings)

- Pricing discounts to ensure products or services are affordable to a target population

- Discounted sales to achieve particular social or environmental objective

When identifying what kinds of social costs you want and need to track, also consider what systems could be implemented to improve the accuracy of distinguishing or estimating social costs. For example, you may want to design time sheets for your supervisory staff that will better track their time utilization between supervisory, counseling, training, fundraising and other administrative duties.

A final point to consider is if there are there any costs borne by outside organizations that are contributing to the success of your business. Even though it is beyond your capacity to track such costs, it is important to recognize and possibly disclose this information if there is a clear relationship and gain. (an example may be subsidized daycare offered to your employees by another community organization)

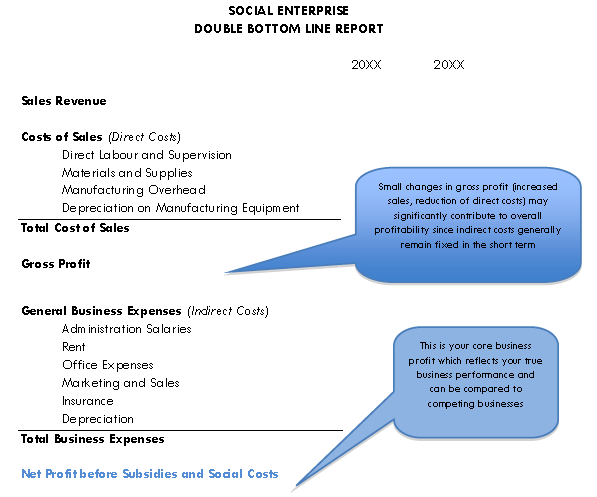

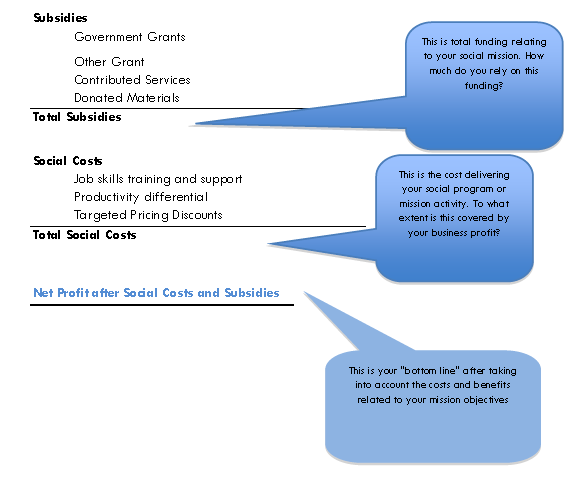

The Double Bottom Line – Illustrated

The following profit and loss presentation, known as “The Double Bottom Line Report”, incorporates many of the concepts discussed in this guide and provides meaningful information to social enterprise stakeholders. The format clearly delineates between traditional business performance and mission performance. Investors will clearly see the social costs associated with your operations and may choose to subsidize them based on the benefits of your mission. You will also clearly see if the cost of achieving your mission objectives are increasing or decreasing over time. This will help managers and stakeholders assess the effectiveness of your programs.

Part 4: Going Forward – Using the True Cost Picture Workbook and other Tools

In this guide, various tools have been referenced that can be found on-line in the Resources library.

True Cost Picture Workbook

The True Cost Picture Workbook is a tool designed to help you implement some of the concepts covered in this guide. The Workbook, in excel spreadsheet form, provides a step-by-step process for “adjusting” existing financial records by identifying all relevant economic inputs (including the value of discounts, donations, volunteer time and costs covered by your non-profit parent agency) and then differentiating “social” costs from “pure business” costs to present a “double bottom line” picture of enterprise performance. Useful ratios are automatically generated to provide further insight into your financial performance. Working through the Workbook will help you clearly see, and thus help you to manage, revenue sources and costs that go into pursuing both your financial and mission objectives.

To help illustrate use of the Workbook, The Stable Roots Landscaping Case Study provides a simple example of a social enterprise and takes it through the True Cost Picture Workbook and supporting tools to develop a Double Bottom Line Report and enterprise snapshot indicators.

The workbook does not replace your accounting system or other financial reports. Rather, it is a tool to identify adjustments and accounting policies that you could choose to implement more permanently in your accounting systems (software) and reporting package.

Financial Ratio Analysis Guide

Financial ratios are a common management tool and useful indicators of an organization's performance and financial situation. The Financial Ratio Analysis Guide is a further resource that can be used to improve your understanding of financial results and trends. The guide provides examples of standard financial ratios used in business analysis and, more importantly, what those ratios tell you about your performance. Review the guide in light of your own financial objectives. Ratios can be customized and incorporated into your financial reporting package or financial snapshot.

Worksheet: Identifying and Measuring Social Costs

The Social Costs Worksheet is designed to help you identify and measure hidden costs and contributions, which are costs that may be important to understanding your financial performance and sustainability, but which you may not consider because you do not pay for them directly.

Part 5: Recommended Resources

General

Financial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really Mean. Karen Berman and Joe Knight. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

The Definitive Guide to Managing the Numbers. Richard Stutely. Prentice Hall, 2003.

Industry Canada, Managing for Business Success

Canada Business, Services for Entrepreneurs

Basic Guide to Financial Management in For-Profits

Business Owner‟s Toolkit, Managing Your Business Finances

Specific to Social Enterprise

True Cost Accounting: The Allocation of Social Costs in Social Purpose Enterprises. Heather Gowdy et al. San Francisco: REDF, 1999. www.redf.org

Guide for Analysis of Social Economy Enterprises. Reseau d'investissement social du Quebec (RISQ), Montreal, Quebec, 2005.

Quest for the Holy Grail: Financial Analysis for the Social Enterprise. M. Whitehead-Bust and V. Dawans. SE Reporter. 302/302 p. 8-10, March 2007.